Eunuchs in Imperial Spaces

by Madi Pehringer

[sketchfab id=”d6074f826e62476c8f8f7c2a1a3b5a02″]

The purpose of this project was to examine the role of a specific gender minority in the Byzantine empire. Using ceremonial documents from the Byzantine empire, we are able to create an interpretation of Chrysotriklinos, the primary throne room in the great palace of Constantinople. This room acted as the focal point regarding the fusion of position and space that this project necessitated. Regarding the traditional thoughts of gender within the Byzantine empire, which at its core is a product of the Roman empire, gender for a majority of the population functioned on the basis of a binary of male on one side and female on the other. Eunuchs were able to fully function within the confines of a rigid gender construction, although they themselves were firmly outside of it: there were several life paths which a Byzantine eunuch might have taken, from monk to warrior to high ranking servant for the imperial family.[1] Although each path presented eunuchs a unique lifestyle and set of expectations for his daily life, the path I chose to study in detail is that of a eunuch who was present in court and who would have acted within the ceremonies that connected church and state. Through this examination, I did not intend to discover what a hypothetical court monk ate for breakfast or how he felt about his role, but rather I intended to discover how he would have functioned within an imperial space. This hypothetical person might be given special rights and considerations in their duties (this will be discussed in more detail later in this essay,) but they still had to navigate a world in which they had no firm place, as someone with a binary gender identity would have. Finding the roles which eunuchs played within the noble courts and palaces was a rather simple task, given several recent secondary sources published on the topic; finding primary sources which discussed their roles was a bit more complicated, given the ‘outsider’ status of eunuchs.

The Book of Ceremonies, which is a Byzantine court document from the tenth century, provides copious detail regarding courtly rituals which were integral in Byzantine noble society. This was valuable for both viewing the roles which eunuchs would have filled in a public, imperial setting, and how their comportment would have had to differ from other members of court with set gender status. To assist in the visualization of this room and the roles which eunuchs would have filled within it, my research partner, Dane Clement, and I have created a 3D model interpretation of Chrysotriklinos, the throne room of the Great Palace at Constantinople.

To begin the visualization portion of the project, Dane and I used primary source analysis. It felt imperative that the sources which were consulted throughout this research be primary sources, and not secondary sources with their own interpretations of the throne room, which potentially could color and alter our own interpretation. For this reason, De Ceremoniis became our primary guiding document. It was chosen purely because the majority of the pomp and ceremony which are recorded in its pages take place in Chrysotriklinos. This fact alone makes the document a wealth of knowledge, not to mention that it numbers over 800 pages, giving plenty of opportunity for the author to insert essential details about the room, its construction, and its decoration. While it’s length was in some regard helpful and reassuring, it was also somewhat of a hindrance: the length of the source combined with the length of the semester did not give us the option to closely read each page and each word. To begin analyzing the De Ceremoniis we used a distance reading technique wherein we selected several key words or phrases, including ‘Constantinople’, ‘throne’, and ‘palace’ to high light sections which might be of interest. These words were selected for their prevalence to our topic and our hypothesis that they would appear in the documents at least once and provide us a detail we could utilize in our construction. From there, selections were taken from each which contained information that was pertinent to the size, shape, and/or general impression of the throne room.

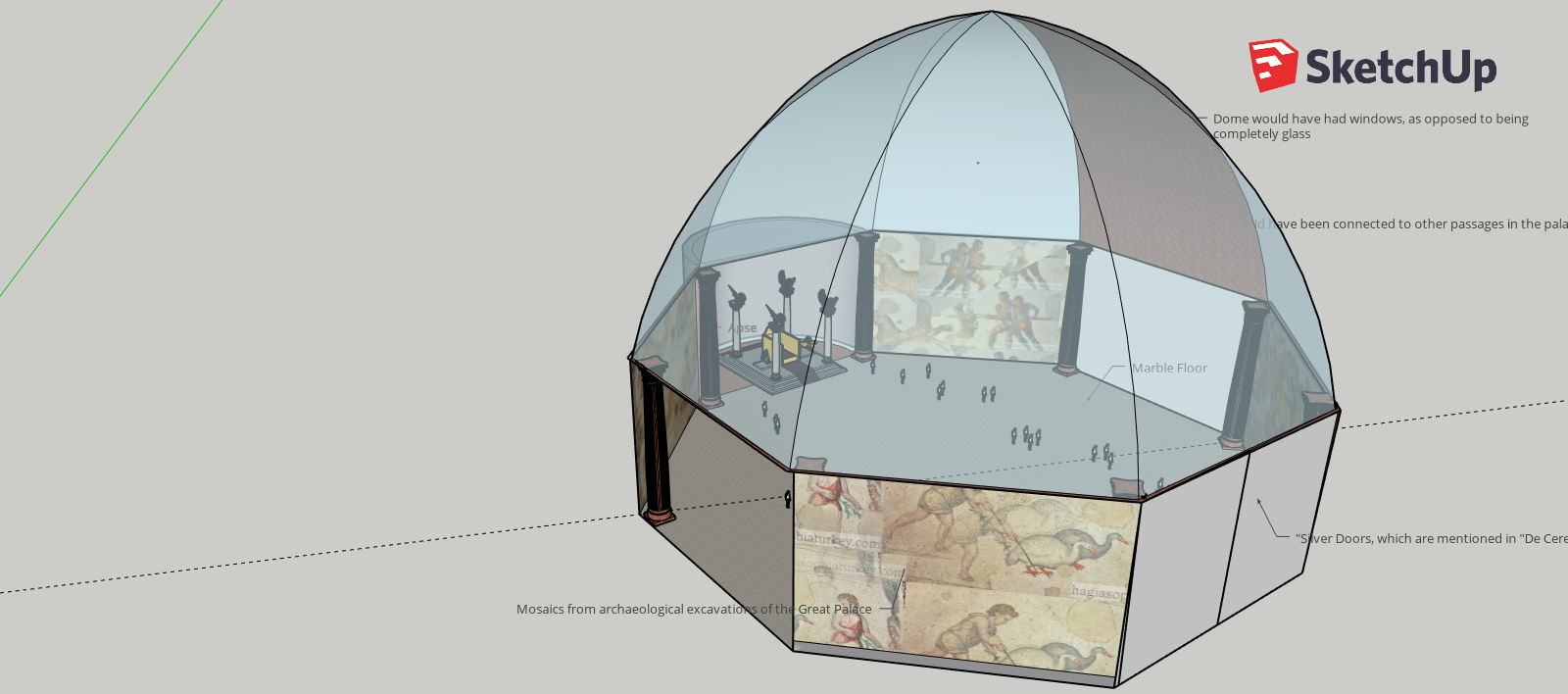

De Ceremoniis, with a more careful reading, provided details aplenty for us to base our model on, although it was not perfect, and there were issued which arose during our analysis and construction. Unfortunately, the document contained no firm numbers pertaining to the scale of the room, nor the exact materials used in its construction. For the scale, we decided on a radius of one hundred feet, given that a number of people would have to be comfortably held in the room at any given time. It also contained little to no information on building materials and types of decorations found in the room, particularly in regard to mosaics. We could, of course, make assumptions based on archaeological records from other rooms in the palace and from other monumental buildings in the city from around the same time period, but we wanted to see if we could find descriptions. Therefore, a search for a second source began. Ibn Battuta, though a later source than De Ceremoniis, provided details from an outside perspective about the great palace and his meeting with the emperor. He confirmed our estimation of scale by using descriptors such as “great” and “large”.[2] While these are by no means numerical confirmations, their use does indicate a room of a certain size. Moreover, Ibn Battuta had been to and seen many impressive places in his travels, so if something was ‘large’ or ‘great’ by his estimation, it more than likely was. He also provided detail about the types of mosaics that were featured on the walls as decoration around the room. Of them, he said, “the walls of which were of mosaic work, in which there were pictures of creatures, both animate and inanimate.”[3] This influenced our decision to put mosaics as wall decoration. The mosaics which are used are extant mosaics found elsewhere in the palace complex. Figure 1 is an example of one of the mosaics used. While they are floor mosaics, they are similar styles to what would have most likely been found on the walls, although some tesserae would have likely been, at least in part, gold, to add more texture as the light hit them. That hypothesis is of course a result of other wall mosaics found in Byzantine constructions, especially those in Hagia Sophia.

Using other Byzantine monuments, especially Hagia Sophia, helped determine what materials were highly valued materials, and which would have been used in high value buildings and constructions. Hagia Sophia, although a church and not an imperial residence, was selected for its opulence and the fact that Chrysotriklinos contains an apse, which are common features found in churches throughout Byzantium. Therefore, it was an appropriate comparative tool to use in our construction. What we learn from using Hagia Sophia is that nature, and especially light, was a hugely important part of Christian Byzantine worldview and aesthetics.[4] Marble was often used for it resemblance to water and the impression of movement that it evokes from a stable structure. This idea of movement in stability is evoked other places as well; the golden tesserae found in the mosaics of Hagia Sophia have a similar effect when the light strikes them.[5] They are, of course, made of a highly valued metal, but the aesthetic gain and the adherence to a Byzantine belief in divinity in light makes it particularly valuable. So, I hypothesize that many of the mosaics also contained gold, and that they would have been placed in positions which allowed the light from the windows above to hit them. Figure 2 depicts the type of windows that would have most likely been present in the throne room. However, due to difficulties using the Sketchup program, we were unable to accurately replicate them, instead opting for a glass dome to indicate the presence of light filtered through glass.

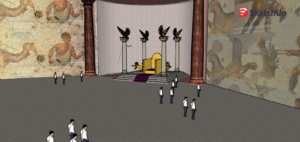

The human figures which are placed in the model came from the Sketchup warehouse, where others can construct components for public use. The chosen figures are not wearing Byzantine garments, but they were chosen specifically for their white attire. It is mentioned in De Ceremoniis that during the Thursday of Renewal Week ritual, everyone from the emperor to the eunuchs wore white garments. Despite our best efforts, it was impossible to find figures in all white, so figures in mostly white were used in the model.

Much of this paper up to this point has been dedicated to the methodology of building our 3D model of Chrsotryklinos. Now, I will be discussing how eunuchs would have fit into and interacted within that space. The research methodology for my work on eunuchs differed significantly from my work on the model. In order to gain a thorough, but relatively rapid, understanding of what exactly a eunuch would have seen as their identity in the Byzantine empire, I turned to a secondary source by Judith Herrin, a renowned Byzantinist with a special interest in eunuchs. According to Herrin, eunuchs in the Byzantine empire were uniquely integrated into their society, when compared to their global counterparts. Eunuchs in China and in Islamic nations, for example, were valued and used in high level political roles, but were not allowed to function within religious and military circles as those in Byzantium were.[6]Those, especially in imperial court, often accumulated vast amounts of wealth and became patrons of the arts, often enriching imperial spaces and capital cities. As we can see from this evidence, eunuchs, while outside the standard norm of gender identity, formed a hugely vital part of imperial society and Byzantine material culture.[7]

I used the Thursday of Renewal Week ceremony as the basis of understanding for eunuch function within court ceremony. It should, of course, be understood that this is simply one case study, and that the functions may change with different specific ceremonies. However, a case study allows us as scholars to glimpse how eunuchs may have utilized this specific space. As mentioned, the figures which appear in the 3D model of Chrysotriklinos are wearing white. This includes the emperor and the patriarch, who are the highest-ranking people in the room.[8] The white color is indicative of renewal from sin, as the name of the ceremony suggests. De Ceremoniis describes the physical position of each person in the room, indicating that the most important people are in the center of the room, and as we move from the center, the importance of members of court decreases. Eunuchs stand behind the emperor, in declining order of their own ranking system.[9] This means that eunuchs were high ranking members of court, even if they were not titled; they were essential to the daily functioning and to the more specialized ceremony. It also tells us that they had their own hierarchy in which they functioned. One eunuch, who would rank high above the other was referred to as the praipositos, and this person acted a messenger between the emperor and the patriarch during the ceremony, leading each in and indicating when the other should enter.[10] It is he who, after the emperor and the patriarch finish their portions of the ceremony, indicates to the rest of the court who should approach to being the ceremony for themselves. Later, after the completion of the ceremony and the subsequent church service, the head eunuch would serve as a steward at the table where the emperor and the patriarch dined together.[11]

As can be seen from the single case study observed from a primary source and the 3D modeled interpretation of the great throne room which they would have mastered, eunuchs were invaluable servants, essential to the proper pomp and ceremony of the Byzantine empire. I hypothesize that had time allowed, a second or even third case study would have revealed a similar outcome, in the roles and utility of eunuchs.

The eunuchs of Byzantium often had unique roles which placed them high in the imperial court. By imaging a physical space which they occupied, we are able to better understand how eunuchs functioned within the greater space of the Byzantine empire.

[1] Herrin, “Eunuchs,” 160.

[2] Ibn Battuta. “Ibn Battuta: Travels in Asia and Africa 1325-1354.” Medieval Internet Sourcebook. Accessed March 2020.

[3] Ibn Battuta. “Ibn Battuta: Travels in Asia and Africa 1325-1354.” Medieval Internet Sourcebook. Accessed March 2020.

[4] Allen, Hagia Sophia, Istanbul.

[5] Ibid

[6] Herrin, “Eunuchs.”

[7] Ibid

[8] “Constantine Porphyrogennetos – The Book of Ceremonies-Brill_compressed.Pdf.”, 90.

[9] Ibid, 91

[10] “Constantine Porphyrogennetos – The Book of Ceremonies-Brill_compressed.Pdf.” 95

[11] Ibid

Sources

Allen, William. Hagia Sophia, Istanbul. Smarthistory.org, n.d. https://smarthistory.org/hagia-sophia-istanbul/.

Battuta, Ibn. “Medieval Sourcebook: Ibn Battuta, Travels in Asia and Africa 1325-1354, Tr. and Ed. H. A. R. Gibb (London: Broadway House, 1929), sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/1354-ibnbattuta.asp.

Cartwright, Mark. “The Great Palace of Constantinople.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, April 28, 2020. https://www.ancient.eu/article/1211/the-great-palace-of-constantinople/.

Hagia Sophia Research Team. “Great Palace Mosaic Museum.” Great Palace Mosaic Museum , 13 Sept. 2018, hagiasophiaturkey.com/great-palace-mosaic-museum/.

Herrin, Judith. “Byzantium: Surprising Life of A Medieval Empire” Princeton University Press 2007: pp 170-184

Porphyrogennetos, Constantine. “The Book of Ceremonies”, trans. Ann Moffatt and Maxeme Tall (with the Greek Edition of the Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae [Bonn, 1829]), Byzantina Australiensia, 18,1 (Canberra: Australian Association for Byzantine Studies, 2012), 2: 830 and 834.

The Oxford Handbook of Byzantine Studies. Oxford University Press, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199252466.001.0001.