A Woman’s Place: Modeling a Byzantine Convent

by Ashley Highland

[sketchfab id=”9064d0f1352b4b84bfff592f2afa8a8b”]

Intro:

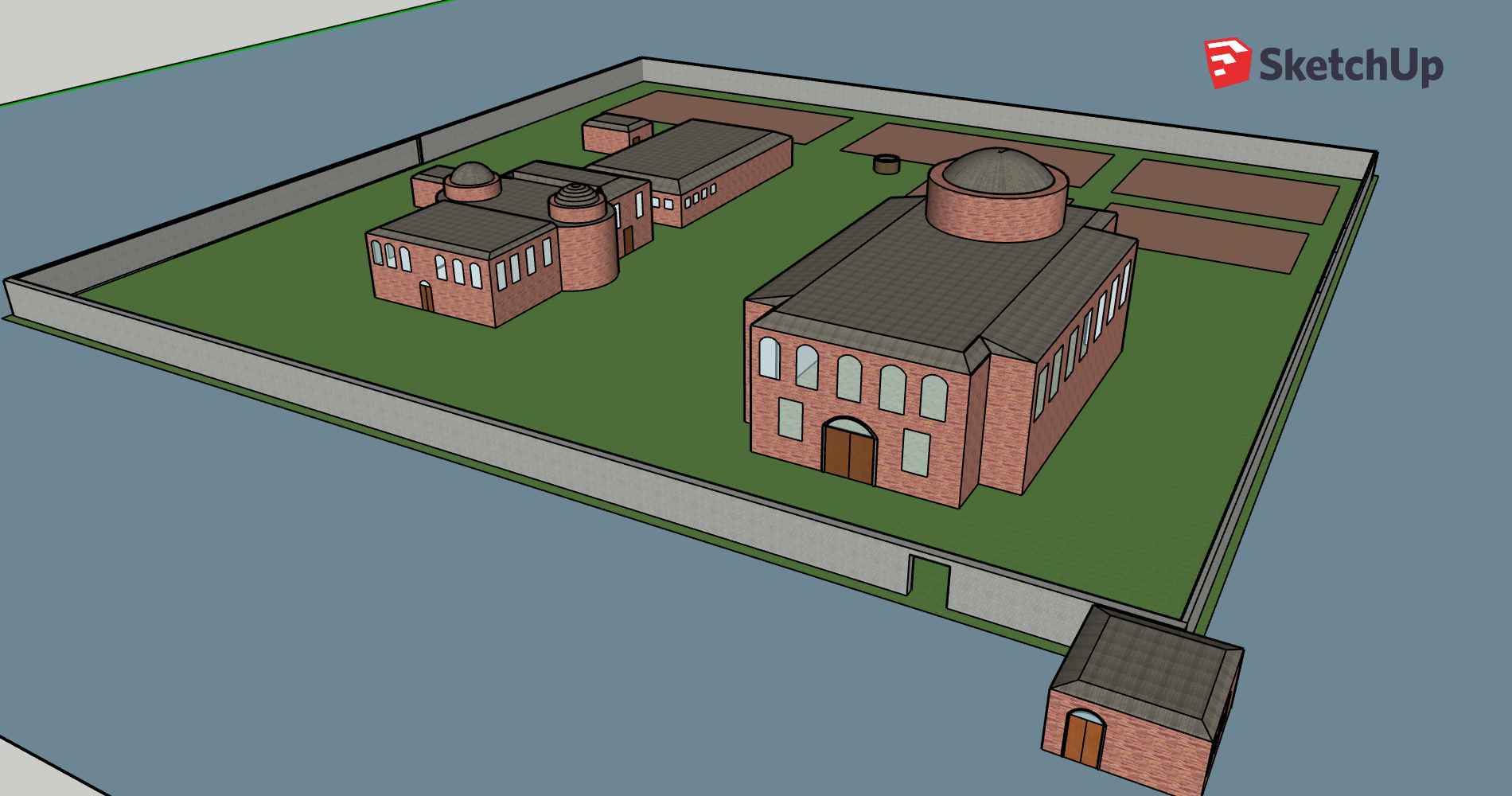

When we think of space, we aren’t often thinking of gendered space. Yet, so many aspects of space are gendered. Our language has words for this: “a woman’s place.” Bathrooms are typically gendered and even universal rooms come with gendered connotations. Throughout history, this is only amplified. How one navigates a space is usually viewed through the perspective of men, assuming the human experience is synonymous with the male experience. Religious spaces are a fascinating intersection of both gender and space. On one hand, christian spaces are deeply gendered with some areas only permitting men to enter. On the other hand, they offered a holy experience to people from all walks of life. While many spaces seemed to be exclusive to men, I could not think of many that were exclusive to women. During this project, I wanted to explore the way a religious space for women might be constructed. Using a combination of written and visual sources, I have constructed a model of a late Byzantine convent using the software Sketchup. The convent reconstruction is not a direct recreation, but an imagining of the kinds of spaces a woman might engage with if she chose monastic life. Through the reconstruction, we can understand the way that space shapes one’s relationship to womanhood.

Obstacles:

When searching for documents I came across two major obstacles. The first, is that there are very few documents on convents specifically. The vast majority of sources concerned male monasteries. Though my primary goal in this project is to see the way women’s’ spaces were distinct, I made the decision to utilize sources on male monasteries. These sources were taken into consideration, but not central to my argument. The next obstacle I came across was the lack of descriptive sources. Something I soon discovered was that it was difficult to find construction plans, or very detailed physical descriptions. The most useful information in this process came from the Dumbarton Oaks Monastic Foundation Documents. Though they did not greatly detail the construction of a site, they did leave many details about the everyday functions of a monastery or convent. In the details, daily tasks or rules were laid out. These made me aware of what buildings and spatial relationships were necessary for everyday functions of the convent.

The Church:

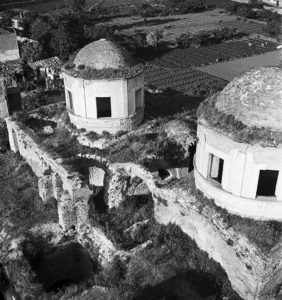

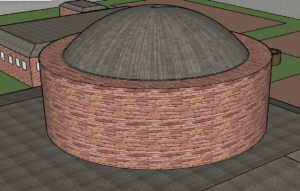

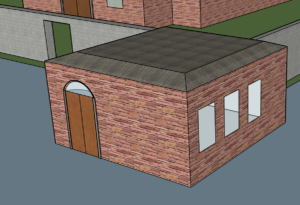

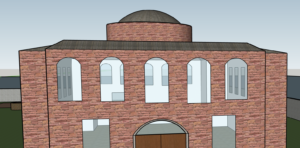

One of the first, and clearest, decisions I made in this model is the inclusion of a central church. When I began, this felt like a “given.” However, the sources informed this decision quite a bit. First, every source I read mentioned a singular, separate place of worship. In Cyril Mango’s The Art of the Byzantine Empire 312-1453: Sources and Documents, the document Vita S Theodorae Thessal 52, actually chronicles a man’s experience visiting an icon in a monastery. However, his description notes a separate building of worship.[1] The writing also references the “narthex,” a specific structure for Byzantine churches at the time. This served as inspiration for the shape of the front of the church. In addition, I elongated the shape of the church, creating a cross-like shape. My shaping of the church was largely based on visual sources. The overall outline of the church was inspired by an image of remains of a Byzantine church in Syria, pictured below.

The image, sourced from Wikimedia Commons, labels this “the Church of Mushraba” and dates the structure from the 6th century. This is much older than the period I planned my model in. However, two of my sources on convents specifically, mention building the convents on top of existing structures that were abandoned.[2] In Luke Levan’s, Late Antique Urban Topography: From Architecture to Human Space, he writes, “Studies of architecture tend to concentrate on new buildings built in Late Antiquity, such as churches. In so doing they neglect older structures, where important traditional activities may or may not still be continuing, such as civil basilicas.”[3] This insight is why I found it important to utilize images of both older buildings, and the new work that may have been inserted afterwards. The largest inspiration for the style of the building would be images of Lips Convent. The Lips Typika informed many other decisions and I felt this would be a good place to find visual trends. The images I selected were found in the David Talbot-Rice collection within the Birmingham East Mediterranean Archive on Flickr. While many images of Lips were taken more recently, I found this set particularly useful. These images were taken in 1937 and are relatively isolated, whereas more modern pictures include surrounding structures. The photographs were useful in seeing what might have been original to the convent before more modern restoration as a Mosque.

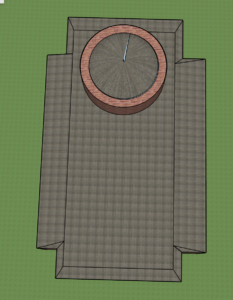

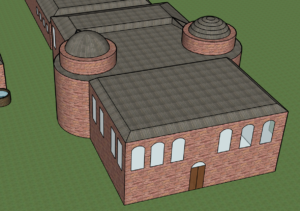

As pictured above, the domes sit atop more square-shaped structures. They are almost cylindrical in shape with the dome top sitting at the peak. I found this to be an important distinction when compared to other churches where the dome is larger and more isolated. Ultimately, this is how I chose to model my domes because it seemed more fitting for a smaller convent church.

Enclosure:

After the church, I noticed that a gate was one of the first things mentioned in the texts. In the account from Mango’s documents, the traveller first notes entering through the gate of the monastery.[4] The Typikon of Theodora Palaiologina for the Convent of Lips in Constantinople, translated by Alice-Mary Talbot mentions a gate as well. One section states, “Thus the gates will be completely shut to those who approach the convent.”[5] This section illuminated two major things: one, there is a gate in the first place, and two, the importance of the gates as a means of enclosure. Again, I worked with the images of lips taken by David Talbot-Rice for visual cues.

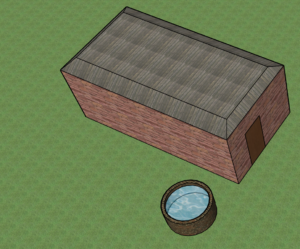

In the images, the border walls seem to have crumbled quite a bit, but there did seem to be a brick wall surrounding the site. In the Typikon of Michael VIII Palaiologos for the Monastery of St. Demetrios of the Palaiologoi-Kellibara in Constantinople, specific reference is made to a building, presumably for the gatekeeper as he writes, “There is the dependency near the gateway.”[6] Both writings on the Lips Convent and the sister convent of Sts. Kosmas and Damian mention the importance of gate enclosure and gatekeepers specifically. This informed my decision to include a separate building just outside the gates of the convent.

Dining and Food:

Another feature I found to be important in multiple documents was an area for dining. Reading three typikons, each addressed specific actions for meal times. In the Typikon for the Convent of Lips in Constantinople, a specific direction was given that “the reading of this testament of mine should be instituted: on the first day it should be read for the length of the dinner hour.”[7] This and other procedures for worship were specified for mealtime. In this sense, mealtimes were more than a simple event. Feasts were highlighted as important holy events as well.[8] With worship and ritual intertwined with mealtimes, I made the decision to make the dining hall another holy place. None of the documents clearly detailed the visual for this space, but their importance led me to follow patterns of the church. A cross like shape is used, with two smaller domes on the side. I imagined these areas could be used as platforms for scripture reading. Their position in the middle would allow the sound to reach all who were seated. The building is long which would allow a long procession of people to enter when needed and in a particular order.

Expanding on the concept of mealtime, food production and storage became another major consideration for my model. The Typikon for Lips was yet again very useful. It addressed a diet for the women, at one time mentioning, “boiled legumes and fresh vegetables with olive oil and shellfish…”[9] I find the mention of fresh vegetables to be particularly important. Though they may have imported vegetables, I imagine that it would have been important for the women of the convent to have their own supply of vegetables. Earlier in the document, it specifies that at least 20 women were workers designated to non liturgical tasks.[10] With the importance of food and meal time, emphasized by a separate communal dining space, I’m making the argument with my model that one of the key jobs would be gardening. I think the emphasis on a somewhat self sustaining community was important. The translator of this document, Alice-Mary Talbot also wrote of the importance of enclosure in her article “Women’s Space in Byzantine Monasteries.” She wrote, “In principle, nuns were cloistered for life and could go out of their convent only in extraordinary circumstances.”[11] Although she details exceptions to this rule, frequent visits to the outside community were not common. This is why I felt the inclusion of farmland was important. In the typikon for the Convent of Sts. Kosmas and Damian in Constantinople, there is direct mention of land usage. The Typikkon describes, “a piece of arable land inside the city of 640 modioi, a vineyard of 65 modioi, a garden at Blanga with the pasturage there.”[12] This solidified the importance of including space for gardening.

Details:

Aside from these larger decisions, I had to make many smaller decisions through the process. I included both a bath house and store room because they were mentioned in various documents.[13] The materials I chose for the outside of the buildings were based on what was available through SketchUp’s warehouse. Brick was the primary choice as it was the clear building material in the visual sources. Windows were fundamental in nearly every building, but especially in the church and dining hall as these spaces represented the most holy areas. Windows were never mentioned specifically in the sources, but I was reminded of Bissera V. Pentcheva’s article, “Hagia Sophia and Multisensory Aesthetics*.” In the article she emphasizes the importance of the windows and lighting in Hagia Sophia. The liturgy would have been conducted at very specific times of the day when light would have spilled into the room.[14] The visual sources gave clues on placement and shape as well. Sizing was difficult to determine. I attempted to keep things in scale, but due to limitations of the project, not all aspects of the model are scaled to every detail.

The Process of Speculation:

The process of modeling itself was a transformative experience in terms of research. Questions arose in the process that would have never occurred to me before. This is where I found that the act of speculation itself is a tool. If I take a moment to speculate about the builders of a convent, I can begin to ask questions about why decisions were made. What might have run through the minds of someone planning a convent? Would they consider how much space women needed in comparison to men? Would they conceive of different uses of a space than I might? This speculation can inform decisions made while modeling and ultimately give a different insight into a Byzantine space. For instance, when considering positioning for the gatehouse, I realized that the gatekeeper likely would not have been a woman. This started with an arbitrary question: “Where should I place the gatehouse? Inside or outside of the walls? Should it be near other living quarters?” One line from a text answered this question. In the Lips typikon they write,

“especially in the case of women of a gentle and weak nature, who need strong protection, inasmuch as they are accustomed to staying at home.”[15]

Through this line of thinking, my entire outlook on the convent changed. I realized the importance of how it was constructed for protection as well as how it was structured to mimic the feel of the home. The gate serves as both a physical protection and a symbolic barrier from the city.

Women and Space:

Ultimately, what was very important to me was how this shaped my understanding of Byzantine women. In a world with very few spaces for women, what might this convent feel like. This led me to consider what an individual woman’s day would be like. Typically, we see disadvantaged groups as a whole. It is not very often that we imagine the life of an individual in those groups the way that we might with people from a dominant group. Through my model, I was able to consider what the walk would be like from a well to the dining hall. I could imagine the strength it would require to carry buckets to a kitchen. Though women are repeatedly viewed as non-laborers, this model gave me the space to understand how women truly did participate in labor. We’re able to imagine what living in proximity to a church would be like. If you’re sleeping 30 yards from holy place, how would that change your relationship to God? I imagine it would strengthen it. These women were also a tight knit community. They ate together, worshipped together, farmed the land together, bathed together, and slept in close proximity. This bond would be nearly impossible in other settings. Other women would not have the same opportunity to live so closely with women outside of the family. This surely created a different relationship to womanhood.

Sources

Footnotes:

[1] Mango, Cyril, The Art of the Byzantine Empire 312-1453: Sources and Documents, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004), 210.

[2] Theodora Palaiologina, Anargyroi: Typikon of Theodora Palaiologina for the Convent of Sts. Kosmas and Damian in Constantinople, trans Alice-Mary Talbot, Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents: A Complete Translation of the Surviving Founders’ Typika and Testaments Volume 1 (Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University 2000), 1290.

[3] Lavan, Luke, William Bowden, and Luke Levan. “Late Antique Urban Topography: From Architecture to Human Space.” In Theory and Practice in Late Antique Archaeology, 171–95. Leiden: Brill, 2003. 179.

[4] Michael VIII Palaiologos, Kellibara I: Typikon of Michael VIII Palaiologos for the Monastery of St. Demetrios of the Palaiologoi-Kellibara in Constantinople, trans George Dennis, Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents: A Complete Translation of the Surviving Founders’ Typika and Testaments Volume 1 (Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University 2000), 1249.

[5] Mango, The Art of the Byzantine Empire. 211.

[6] Theodora Palaiologina, Lips: Typikon of Theodora Palaiologina for the Convent of Lips in Constantinople, trans Alice-Mary Talbot, Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents: A Complete Translation of the Surviving Founders’ Typika and Testaments Volume 1 (Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University 2000), 1270.

[7] Typikon of Michael VIII Palaiologos for the Monastery of St. Demetrios, 1292.

[8] Typikon of Theodora Palaiologina for the Convent of Lips in Constantinople, 1275.

[9] Ibid., 1257.

[10] Talbot, Alice-Mary. “Womens Space in Byzantine Monasteries.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 52 (1998), 119.

[11] Typikon of Theodora Palaiologina for the Convent of Sts. Kosmas and Damian in Constantinople, 1292.

[12] Typikon of Theodora Palaiologina for the Convent of Lips in Constantinople, 1268.

[13] Ibid., 1262.

[14] Pentcheva, Bissera V. “Hagia Sophia and Multisensory Aesthetics.” (Gesta 50, no. 2, 2011), 95.

[15] Typikon of Theodora Palaiologina for the Convent of Lips in Constantinople, 1266.

Written Sources:

Lavan, Luke, William Bowden, and Luke Levan. “LATE ANTIQUE URBAN TOPOGRAPHY: FROM ARCHITECTURE TO HUMAN SPACE.” In Theory and Practice in Late Antique Archaeology, 171–95. Leiden: Brill, 2003.

Mango, Cyril. The Art of the Byzantine Empire 312-1453: Sources and Documents. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004.

Michael VIII Palaiologos, Kellibara I: Typikon of Michael VIII Palaiologos for the Monastery of

St. Demetrios of the Palaiologoi-Kellibara in Constantinople, trans George Dennis, Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents: A Complete Translation of the Surviving Founders’ Typika and Testaments Volume 1 (Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University 2000)

Pentcheva, Bissera V. “Hagia Sophia and Multisensory Aesthetics.” Gesta 50, no. 2 (2011): 93-111.

Talbot, Alice-Mary. “Womens Space in Byzantine Monasteries.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 52 (1998). https://doi.org/10.2307/1291779.

Theodora Palaiologina, Lips: Typikon of Theodora Palaiologina for the Convent of Lips in Constantinople, trans Alice-Mary Talbot, Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents: A

Complete Translation of the Surviving Founders’ Typika and Testaments Volume 1 (Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University 2000) Theodora Palaiologina, Anargyroi: Typikon of Theodora Palaiologina for the Convent of Sts. Kosmas and Damian in Constantinople, trans Alice-Mary Talbot, Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents: A Complete Translation of the Surviving Founders’ Typika and Testaments Volume 1 (Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University 2000)

Visual Sources:

Figure 1: “Byzantine church of Mushraba Syria” 2005, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Figure 2 & 3: Photographs of Lips Convent in Constantinople taken by David Talbot-Rice, 1937. Courtesy of the David Tablot-Rice collection within the Birmingham East Mediterranean Archive on Flickr.