Byzantine Bronze: Visualizing the Chalkê Gate

by Ethan Cheers

[sketchfab id=”d2663d2f16dc4094b576c7894cfd0eeb”]

Introduction

The Byzantine Empire is unique in that its lifespan spread across twelve different centuries, from the Late Antiquity to the Middle Ages. From 330-1453 CE the Byzantine Empire was a force in Afro-Eurasia where they consistently controlled vast masses of land containing multitudes of different cultures from the Middle East, Medditeranean, and European traditions. This has resulted in the Byzantine Empire being rich in culture, archaeology, and art. Often overlooked by historians, the historical impact of the Byzantine Empire is often not recognized. This project attempts to visualize a historical Byzantine site through the application of relevant primary sources. In particular, this research will focus on the modeling of the Chalkê, a building that served as the gate and main entrance to the Imperial Palace, as it stood in the late 6th century.

The Chalkê Gate is named for its use of bronze on its doors and roof (Chalkê translates to bronze in English). It was first built sometime between the reign of Constantine and Justinian (4th-6th centuries). When the gate burned down during the Nika riots in 532 CE, Justinian rebuilt it and that iteration of the Chalkê endured for decades. Shortly after its rebuild, an icon of Christ was painted on the front of the gate. This particular icon would become known as Christos Chalkitês. While seemingly historically unimportant for centuries until it became a proxy for the iconoclasm debate. Iconoclasm was a debate raging through the Byzantine Empire in the 8th and 9th centuries. On one side are the iconoclasts who believed that representations of Christ or any other religious figure was unholy and pagan-like, these people often destroyed icons and other religious artifacts. On the other hand are the iconophiles who support the use of representations of religious figures as icons. In the early-mid 8th century Emperor Leo III, an iconoclast, ordered the removal and destruction of Christos Chalkitês from the Chalkê Gate and replaced it with an image of a cross. This marked the beginning of a prohibition of icons and sparked rioting in the city. The Chalkê became an epicenter of this debate as some of the people sent to take the icon down were killed. Throughout the next century Christos Chalkitês was repainted and taken down again, its survival depended on the ideology of the ruling emperor, whether they were an iconoclast or iconophile.

The Chalkê was not only the main entrance but it also served as a proxy for the Byzantine Iconoclastic debate. It was this proxy status that drove me to want to use it as the topic of my study. The initial research questions I had focused on the Chalkê in relation to Tim Cresswell’s, Place: an Introduction. In his book, Creswell discusses the power of a place. He explains that the effect of the Tiananmen Square protest was amplified due to the place of protest, Tiananmen Square, having deep cultural meaning and the building itself being surrounded by some of the most important buildings of the ruling government [1]. If this protest were to happen anywhere else it may not have been as significant. The Chalke served as an epicenter for protest not only during the Byzantine Iconoclasm debate but also during the Nika riots and many other tumultuous events. What was the significance of the Chalke that it was often the setting for these protests?

Methods

To begin the 3D model, I began researching intensively for primary sources that I could base my model on. It was not easy, the Chalkê Gate is suspected to have been destroyed in the 13th century. Because of this, there are sparse accounts of the Chalke as experienced by Byzantines centuries ago. To counteract this, I found one solid secondary source in Mango’s Brazen House, a study of the Chalkê Gate. This secondary source provided me with a bountiful pool of primary sources. I had concerns about Brazen House potentially creating an unwanted bias within me to interpret the Chalkê similarly to how Mango does in my own visualization. Thankfully, that is not how Mango wrote her book, because in Brazen House primary sources are introduced to study the Chalkê and are often presented in a manner that respects all arguments that have been made in the research surrounding the Chalkê Gate. This allowed me to continue my own interpretation whilst streamlining my primary source search. After finding these primary sources embedded into Brazen House I then used them to craft my 3D model. This was not how I found every source but it provided me with a strong groundwork to begin my research.

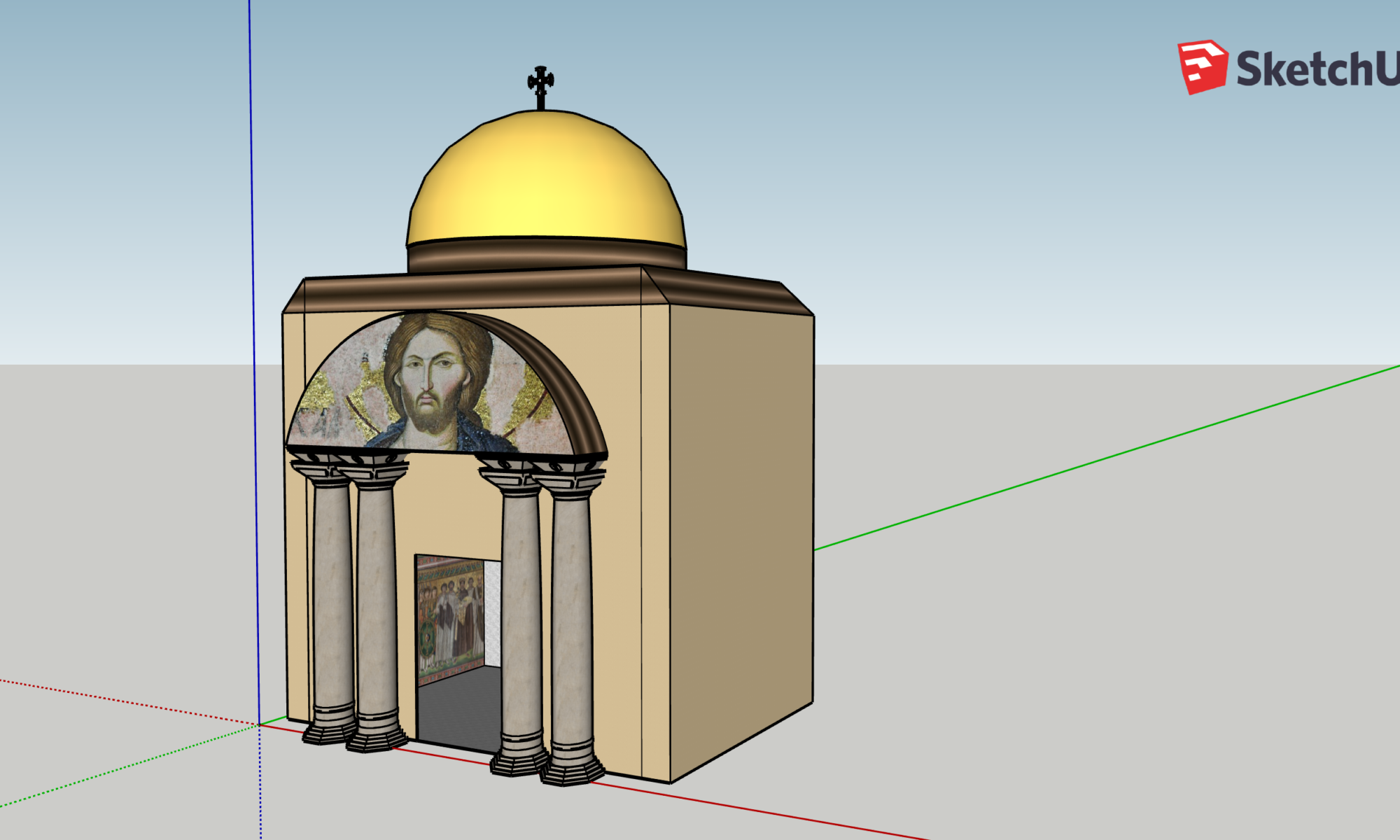

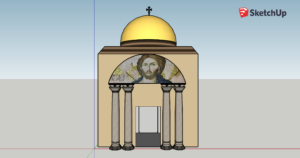

There are not many primary sources surrounding the Chalkê Gate in existence. Luckily, Procopius’ De Aedificiis still survives today and provides a detailed description of, mainly, the interior of the Chalkê as built by Emperor Justinian I. Procopious writes that the Chalkê was rectangular in shape topped with a dome set on pendentives typical of Byzantine architecture from the period [2]. I made the model of the Chalkê rectangular but I could not, however, create pendentives in my model and had to omit them. But, thanks to the 3D Warehouse tool in SketchUp I was able to crowdsource for a Byzantine style dome. I used the dome pictured in the model and on the inside of the dome is a mosaic of Christ Pantocrator, a famous icon that is typical of Byzantium (see Figure 1).

Next to the dome is the bronze tiling of the Chalkê, for this I also used the Warehouse tool in order to obtain a bronze texture. Procopius also describes the interior as decorated in tricolor marble and mosaics adorning the walls. In particular, Procopius mentions that the mosaics represented Justinian I’s great victories [3]. I used the SketchUp materials to make the texture of the floors and walls a tricolor marble. Following Procopius’ description even more, I then placed a famous mosaic of Justinian I on the westernmost wall. The other textual primary source I encountered in my research was De Ceremoniis, a Byzantine Empire commissioned text describing the ceremonial and ritual protocol of the Byzantine Empire. As previously mentioned, the Chalkê was the main entrance to the Imperial Palace, because of this it also served as the ceremonial entrance and exit as well. Because of this, the De Ceremoniis provides a great insight into the architectural orientation of the Chalkê as it details exact routes in which ceremonial processions would take place. This text mainly helped me decide on the size I wanted my model to be. Throughout De Ceremoniis processions are described as containing horse drawn chariots carrying the Emperor and members of the court [4]. Because of this I decided to use the average height of a horse (five to six feet) and postulated that a ceremonial carriage may be up to two or three times larger than the horses and that it would take multiple horses to pull that chariot. Based on this information gathered from the De Ceremoniis I made the door or gate of the Chalkê thirty feet tall, tall enough for functional use and tall enough to satisfy the grandeur of Byzantine Imperial architecture.

I also used an abundance of visual sources. In both De Aedificiis and in Cyril Mango’s Brazen House there are mentions of pillars or piers as a structural element of the Chalkê [5][6]. Pillars were very popular in the Roman empire and as the Byzantine Empire was an extension of the Roman empire, pillars were prevalent in Byzantium as well. Due to my lack of expertise in the software SketchUp that was used to create this model I had to resort to using pre-made Byzantine style pillars that I encountered in the “3D Warehouse”. I was pleased with the accuracy of these pillars as they displayed the typical Christian Orthodox symbols at the crown of the pillar that are often found in Byzantine architecture. I cross-referenced the 3D warehouse pillar with many images of Byzantine architecture to verify the similarity of the pillars (see Figure 3).

As I mentioned before, I used a 3D Warehouse dome for my model but the exterior appearance of the dome including the cross on top originate from my comparative use of domes from the Hagia Sophia (see Figure 4). These can be used comparatively because the domes on the Hagia Sophia were constructed in the same era as the Chalkê gate. Both Imperial constructed buildings were burnt down during the Nika riots and rebuilt shortly thereafter by Justinian I. Another aspect of my model that originates from visual sources is the Mosaic that is on the westernmost wall. I mentioned previously that Procopius maintains that the walls in the Chalkê contained many mosaics depicting the power and success of Justinian I. Since I cannot recreate a mosaic in SketchUp I decided to include an actual historical mosaic of Justinian for one of the walls to add authenticity to my model. I chose the famous Justinian mosaic from the Basilica of San Vitale (see Figure 5).

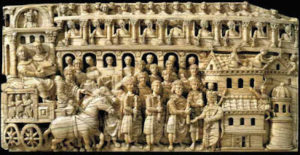

Another visual source that aided me whilst creating my 3D model was the famous Trier Ivory (see figure 6). This helped me when I was contemplating the dimensions of the building and the door. The Trier Ivory depicts a typical Byzantine Imperial procession that would enter and exit the palace grounds via the Chalkê. This helped me deduce that I would need two symmetrical entrances and exits from the gate. What I mainly took away from this source was the sheer size of the processions, this led me to creating a very large entrance to accommodate for this.

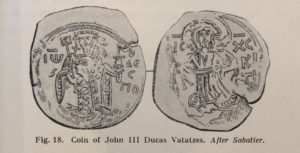

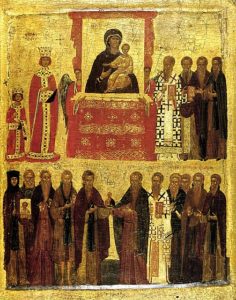

From the beginning, the focal point of my research was the Chalkê itself but also the famous icon of Christos Chalkitês (or the Chalke Christ). In order to represent this all-important icon on my model I decided to use the same method I had done for the interior mosaic. I chose an image based on my research to represent that aspect of the model. Nobody knows who painted the original Chalke Christ and, on top of that, there are very few accounts of the appearance of the Chalke Christ. So, in order to decide how to interpret the Chalke Christ in my visualization of the Chalke I turned to a variety of visual and material sources. First, there are many coins that depict the Chalke Christ as a standing figure with a surrounding halo and cross, similar to the Christ Pantocrator that was so prevalent in byzantine culture. Specifically, the Coin of John III Ducas Vatatzes [7] depicts the late emperor as being crowned by the Chalke Christ (see Figure 7). The Chalke Chist in this image appears to be standing and his head seems to be surrounded by a halo with a symbol of the cross as well. The Chalke Christ as portrayed by the coins is seemingly confirmed by the Icon of the Triumph of Orthodoxy (see Figure 8). This is a late 14th-early 15th century icon that depicts the “Triumph of Orthodoxy” at the conclusion of the last Iconoclastic period where they ceremoniously restored icons to the church. In this depiction is St. Theodosia of Constantinople. She is one of the women who had killed an officer by shaking his ladder while he attempted to take down the Chalke Christ under orders from iconoclast Emperor Leo III. She was later executed and was later recognized as a martyr and a saint. In the icon of the “Triumph of Orthodoxy” St. Theodosia is seen on the bottom left holding an icon of the Chalke Christ. This depiction of the Chalke Christ is very similar to the previously mentioned coin and other historians depiction of the iconography of the Chalke Christ. Because of the information I gathered from my sources I decided to use an icon similar to Christ Pantocrator from the Chora Church located in Constantinople [8].

Findings

Throughout my research and visualizing of the Chalkê Gate there were a couple revelations. Visualizing the Chalkê unearthed for myself just how grandiose and awe striking the sheer size and architecture of the building. I did not know much about the building when I first started other than its role in Byzantine Iconoclasm. As my research continued I started to realize more and more just how large the model would have to be, any human would pale in comparison to the size of the Chalkê Gate. It was this revelation that helped me discover that the importance of the Chalkê was not only in its role during Byzantine Iconoclasm but its role in demonstrating the strength and grandeur of the empire. There is a reason that the gate plays such a large role in the ceremonial processions detailed in De Ceremoniis… the gate was an important part of all Byzantine life, not just royal life. Another potential research question that arose during my research was how men, women, different races, and different socioeconomic classes would experience the Chalkê Gate. Were there restrictions of any type in this area of Constantinople? These thoughts could be expanded to the entire surrounding Augustaion which includes many significant Byzantine monuments and buildings.

When I first began the journey of this research I was mainly interested in the “power and significance of place” as described by Tim Cresswell in Place: an Introduction. More specifically in relation to the Chalkê Gate and its role in Byzantine protests and Iconoclasm. When it comes to Byzantine Iconoclasm, the Chalkê seems to be at the epicenter of this debate. The Chalke Christ even makes an appearance in the icon “Triumph of Orthodoxy”, which depicts the end of iconoclasm and the official return of icons, created around eight centuries after the protests at the Chalkê took place. The question that led me into this research is, why? There were icons across the empire being destroyed during the iconoclastic movement. I found during my research and visualization that the significance of place when it comes to the Chalkê Gate and Byzantine Iconoclasm is the symbolic tie between the empire, religion, and its citizens. The Byzantine people, or at the least Byzantine culture, was intrinsically Orthodox Christianity. The role that Eastern Orthodoxy plays in both government and culture cannot be understated. The Chalkê symbolically tied all three of these together. Not only was the Chalkê the portal between the royal court and the people of Constantinople, it was also symbolic of the importance of religion to both the empire and its citizens. When the emperor, the head of the Byzantine Empire, orders the destruction of an icon of Christ it may please Iconoclasts but to others it was the destruction of the Empire’s ties to Orthodoxy traditions that many of its citizens followed.

My interpretation of the Chalkê is an argument in and of itself. With such little information available about the appearance of the gate a lot of the choices I made were subjective. This is a great reminder that the little choices we make when doing historical research, writing, modeling, etc, all make up a subjective argument about our past. On very few occasions can we be certain of all our historical assertions.

Conclusion

When this research assignment was first introduced to me I was so interested in the concept of recreating something that only exists historically. What I was unaware of was the challenges I would face. The Chalkê Gate’s appearance is famously unknown and the last time it existed was over seven centuries ago. Yet, visualizing the Chalkê through a 3D model using corresponding research helped me learn a lot about not only the Chalkê but also taught me alot about the practice of history and historical research in general. Through this project I’ve found that the significance of place applies even to protests and movements over a thousand years ago. On top of this, the importance of religion in Byzantine culture was reinforced throughout my research. These findings may potentially inspire future research on the importance of the settings of other important moments in Byzantine history. For example, the Hagia Sophia was burnt down in protest two times in less than one hundred years before it would go on to survive to this day, 1500 years after its construction under Justinian. What was the significance of the previous two protests that led to the Hagia Sophia’s destruction and then why, a monument seemingly so volatile, could stay around for over a millennium. The research doesn’t end with my interpretation. There will never be a consensus on an interpretation of the Chalkê Gate but by continuing the research and interpretations, historians can learn more about the invaluable culture and time period of the Byzantine Empire.

[1] Tim Cresswell, Place an Introduction (Chicester: Wiley Blackwell, 2015), p.1-21)

[2] De aedificiis, I, x, 12-15

[3] ibid

[4] The Book of Ceremonies (Canberra: Australian Association for Byzantine Studies, 2012)

[5] De aedificiis, I, x, 12-15

[6] Cyril Mango, The Brazen House: a Study of the Vestibule of the Imperial Palace of Constantinople p.30

[7] ibid p.133

[8] “Chora Museum Istanbul,” Chora Museum Istanbul, https://www.choramuseum.com/

Bibliography