Byzantines, Books, and Buildings: Visualization of the Stoudios Scriptorium

Katelin Ivey

[sketchfab id=”eb34f6cfc87c4c668d953b85a82b950d”]

Introduction

The Byzantine Empire spanned a vast amount of territory and time, so it is to be expected that traces of Byzantine life are still being uncovered and studied more than five hundred years after the end of the era. In order to better understand the Byzantines, it is important to understand the spaces in which they lived for more than a thousand years. This project attempts to create a visualization of a particular Byzantine space or place chiefly through the interpretation of primary sources. These sources be they archaeological, visual, or textual were examined with a critical lens that was applied to inform educated interpretations as to what these spaces might have looked like during a particular period or to a particular group of people. This study in particular models what the scriptorium at the Monastery of St. John the Forerunner at Stoudios, more commonly called the Stoudios Monastery, in Constantinople would have looked like during the 11th century.

The Stoudios Monastery in Constantinople, built during late 5th century, contained one of the most famous scriptoriums in all of the Byzantine Empire. A scriptorium was a complex, usually within a monastery, that produced hand illuminated manuscripts. During this era, the generated texts were largely religious and devotional ones. Though many manuscripts have survived to present day, there is very little available information on the lives of the scribes who produced them, and even less about the spaces that they worked in. In the case of the Stoudios Monastery in particular, there is almost no surviving archaeological evidence as the structure of the complex was devastated by numerous fires and earthquakes. Only the main church stands today, and even it is in ruins.

Since there is very little surviving definitive evidence as to what the entire monastery looked like, let alone the scriptorium in particular, a variety of sources were employed in order to guide the visualization. These sources include letters written by scribes and excerpts from the colophons and margins in which the copyists made note of their working conditions, visual evidence from manuscripts that depict authors at work, and archaeological remains from the Stoudios Monastery as well as those from other scriptoriums. This information was then combined and employed in the creation of a model using the modeling software Sketchup.

The scriptorium at the Stoudios Monastery was chosen because it had been one of the most important players in manuscript production during the Byzantine period. Yet, compared to the number of extant books from the scriptorium, there is still frustratingly little known about the lives of the people who created them and the spaces in which they devoted time to their craft. This visualization aims to reveal what these spaces would have looked like to the best ability of the surviving sources. By understanding what these spaces would have looked like, it then becomes possible to begin to understand more about the people who populated these spaces and how they interacted with them. Coupled with surviving sources, the model reveals that in many cases the producers of these vibrant books spent their days in very austere conditions.

Model

Methods

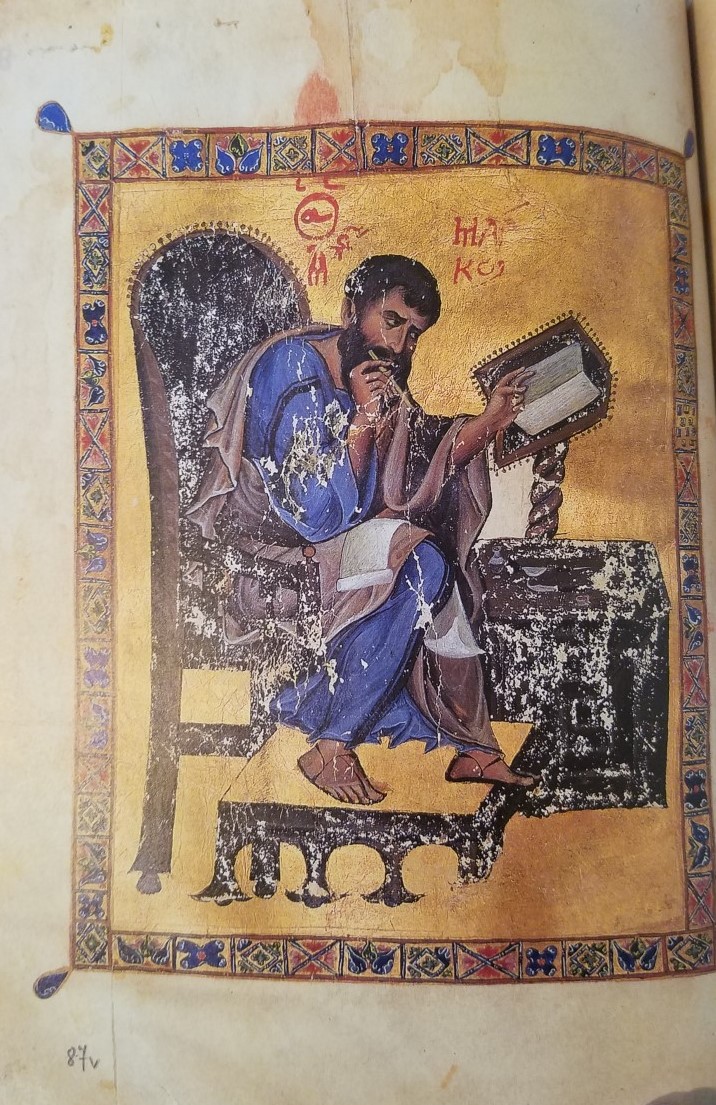

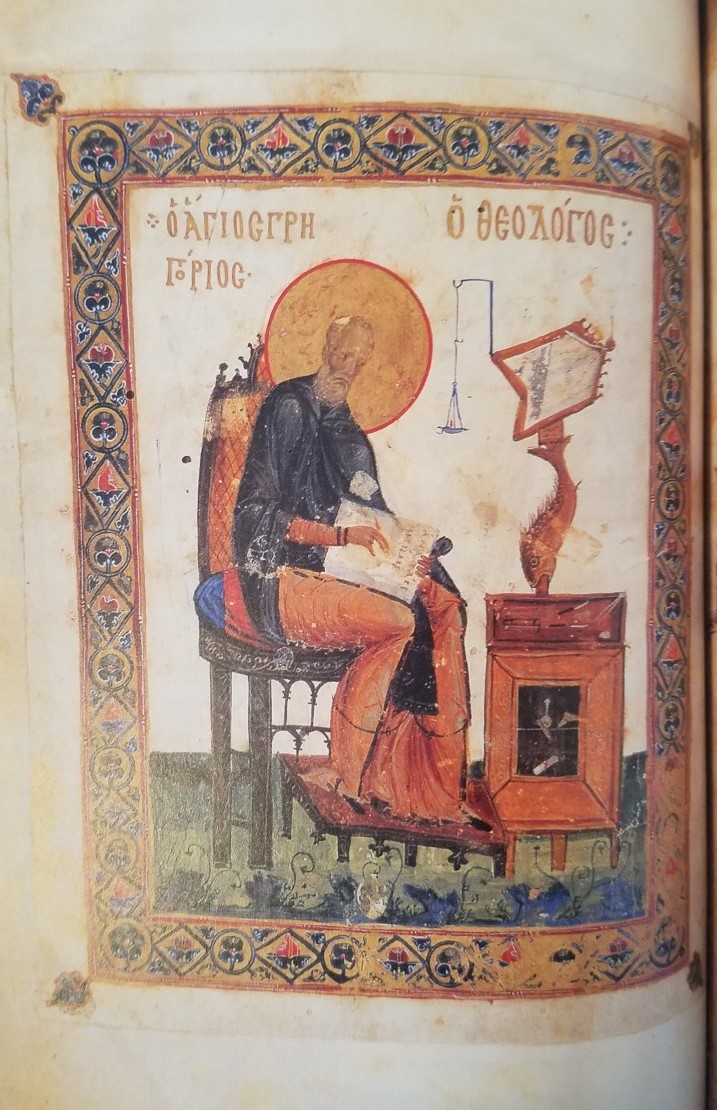

As mentioned above, several types of evidence were used for the visualization of the scriptorium. Perhaps the most obvious, and useful, source was the visual evidence contained within the manuscripts themselves. There are many surviving images within these texts that depict famous authors like St. Luke and St. Gregory at work. Figure 1 shows St. Mark as he worked on his Gospel, which was important because not only does it show Mark in the act of writing, but also the station at which he worked. Several of these images were contained in John Lowden’s Early Christian & Byzantine Art, an art history text with a particular focus on manuscripts. These images were particularly useful as even though they depict saints at work and not the common copyist, they still provide insight to the materials that were available to the copyist and the way in which they were positioned as they wrote. For example, Figure 1 shows the copyists writing with the parchment braced on their lap rather than on the table that is nearby. Rather the supplies were set on the nearby table and the writing was done bent over on one’s lap. Images like this one provided key insight into how the writing process would have looked for one working in a scriptorium.

Another important source was textual evidence. This evidence ranged from contemporary writings that also sought to examine the scribe’s lives and working conditions to excerpts from the colophons of manuscripts in which scribes themselves described, and often complained, about the conditions in which they worked in.[1] From these descriptions that I was able to extrapolate about the working conditions that the copyists endured as they, “were obliged to spend long hours away from the warmth of the stove and who often complained … that they were cold or that the dinner hour was a long way off …”[2] These comments provide insight into the things that were present or lacking from the scriptorium. As a number of scribes complained about the cold, it was likely that the room was devoid of all open flames or other heat sources which could have possibly been harmful to the parchment if exposed. This lack of heating was then considered when building the model, in which there is no fireplace or other source of heat present in the room.

Letters written by scribes also give insight into their workplace. These sources detail copyists filling out contracts and ordering supplies. In one such letter a monk requests a particular size and quality of vellum to be bought for the monastery.[3] Notes like this reveal that monasteries did not always produce their own parchment and vellum, requiring them to order it from outside and divulging important details about daily operations in the monastery and their sourcing of materials.

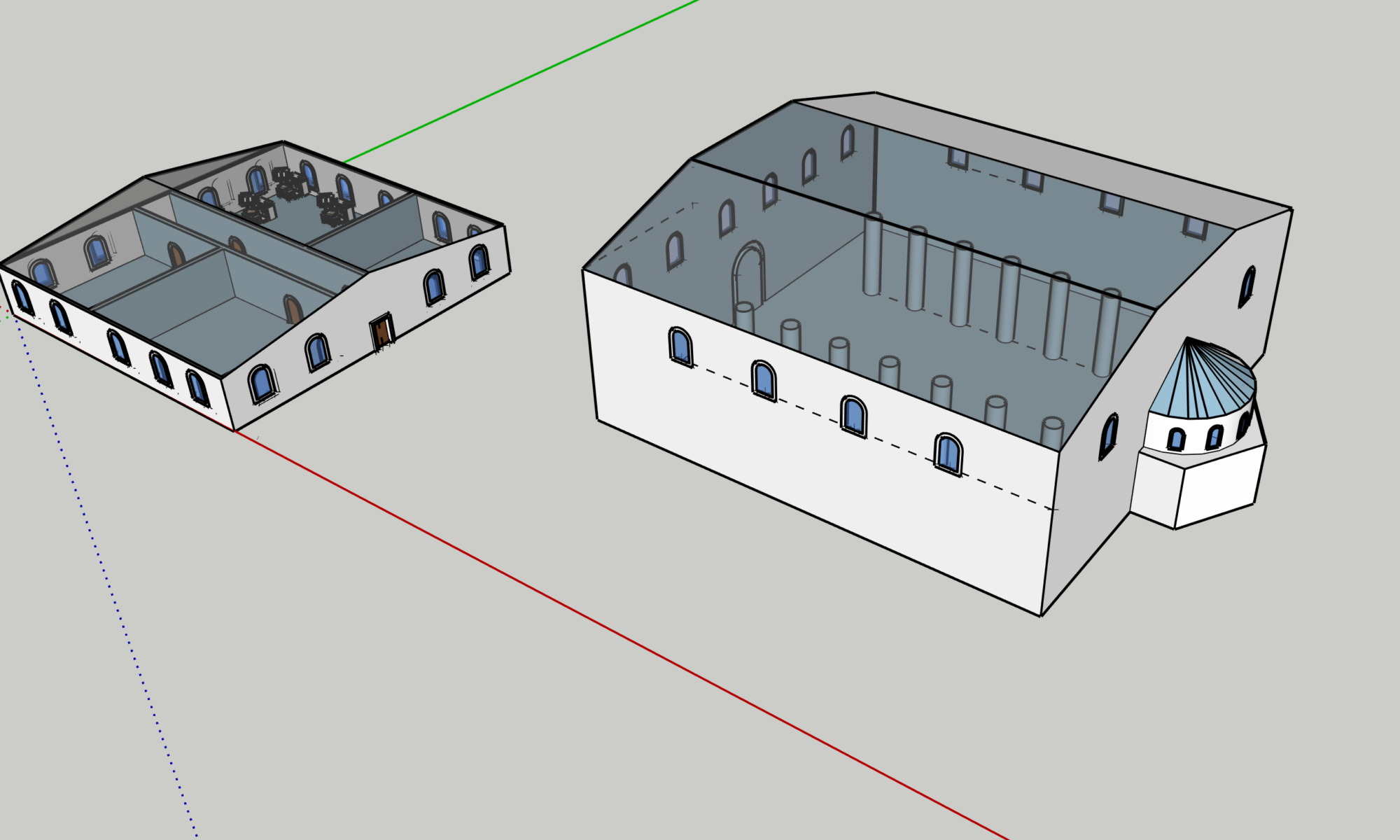

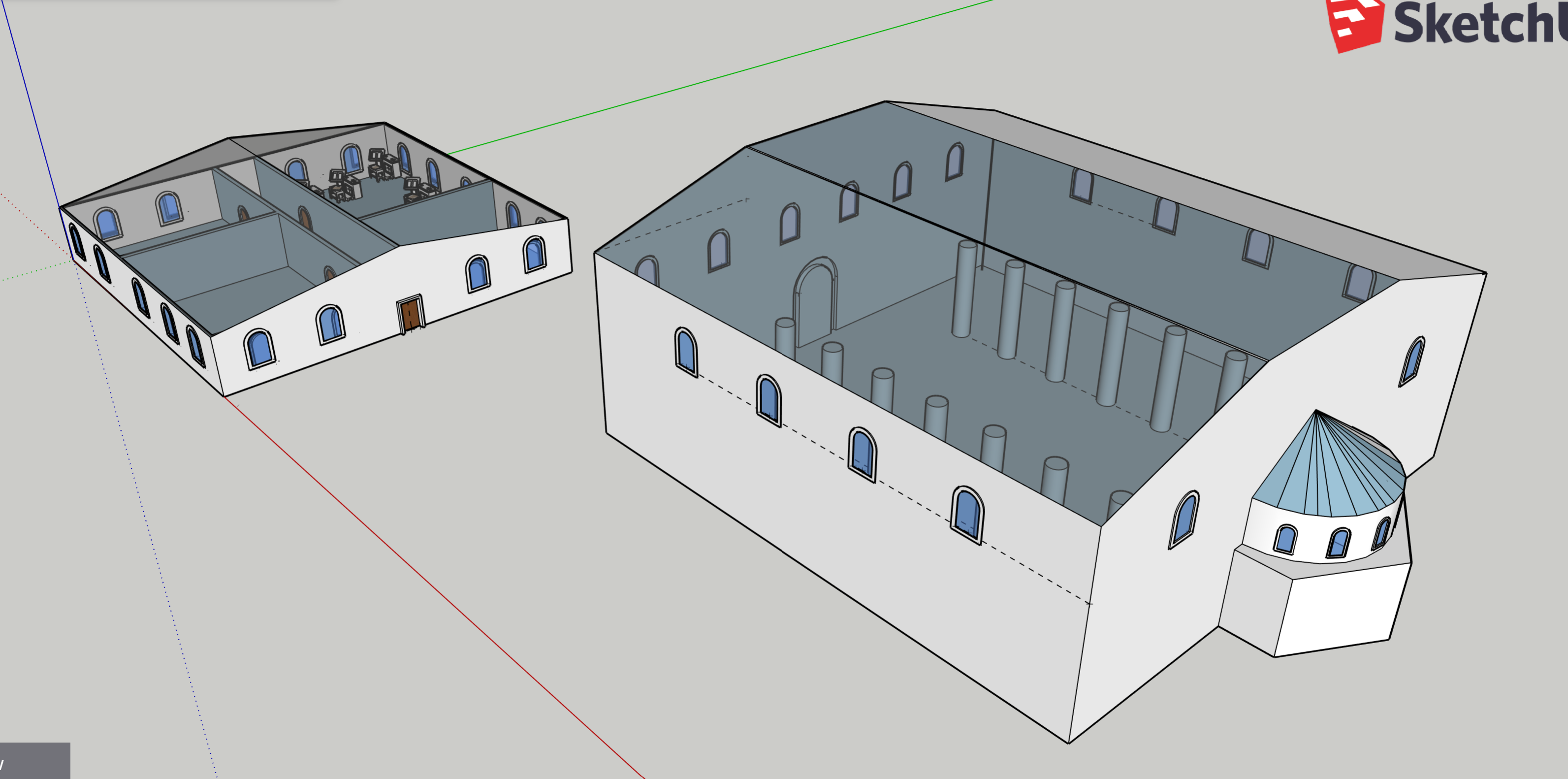

Though there is very little surviving of the Stoudios Monastery, archeological evidence still played an important role in the creation of the model. The typika for the Stoudios Monastery contained in Dumbarton Oaks’ Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents contained a brief mention as to where the auxiliary buildings of the monastery were situated in relation to the abbey.[4] Photos of the surviving abbey were also used in order to model what the building would have looked like before it fell to ruins. Figure 2 shows a view of the abbey’s apse, which had an octagonal base and a cylindrical upper level. With these reference photos of the actual site it was possible to create a model of the Stoudios Monastery that was more accurate, especially given the lack of written sources describing what the monastery complex looked like.

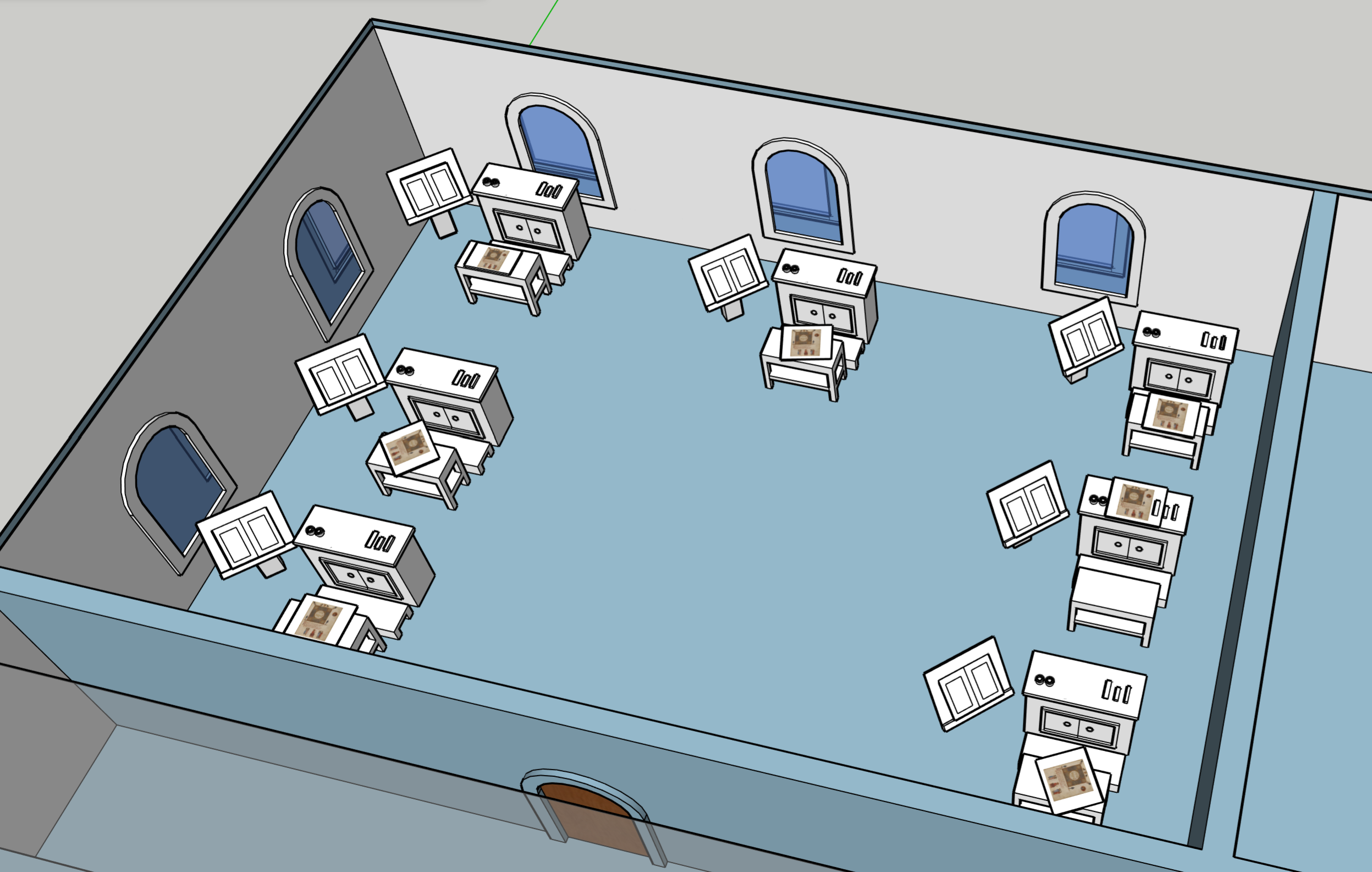

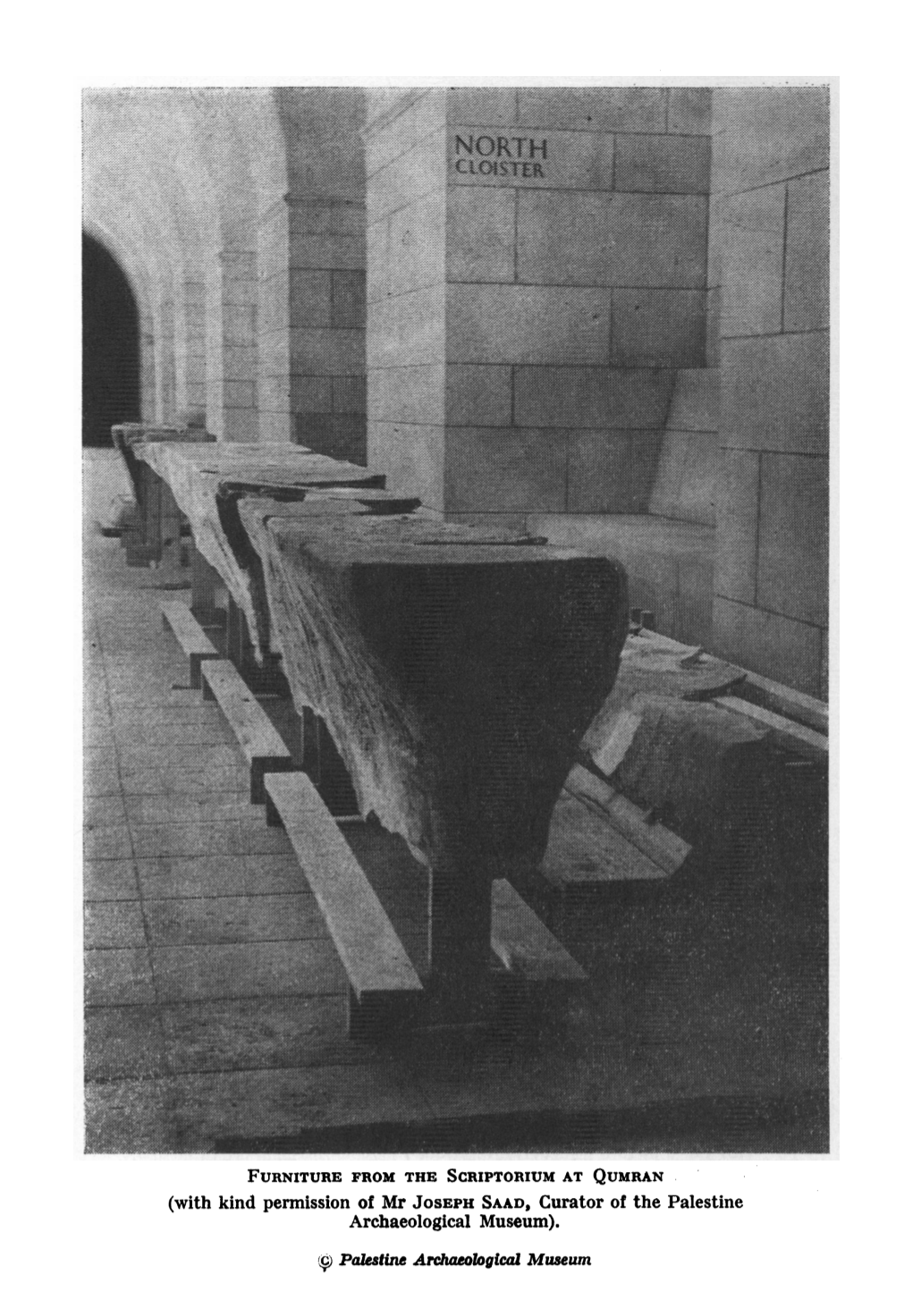

Also useful were the archaeological remains from scriptorium at Khirbet Qumran.[5] Excavations of the site in the 1950s uncovered a scriptorium compete with furniture and pieces of the scribe’s tools, as well as the dimensions of the room itself. The remains of this scriptorium were then used as a base for the scriptorium at Stoudios, both for the furnishings in the room in particular and the size of the room in general. See Figure 3 for an example of the furniture in the scriptorium at Qumran. Information from the archeological remains was then combined with the other sources in an attempt to create a coherent picture of what the scriptorium at the Stoudios Monastery would have looked like.

In creating this model, decisions had to be made about the interpretation of evidence. One of the most obvious being the location and the layout of the scriptorium itself, since there is no primary source available for the Stoudios Monastery that explicitly describes it. The most definitive evidence about the monastery comes from the commentary on Theodore the Studite’s typika for the monastery, in which is it stated that “the monastery must have been located along the south side of the church’s atrium, but only a cistern remains from that part of the foundation.”[6] This description gave a clue as to where the other buildings in the complex would have been located, but did nothing to distinguish their layout or finer details. Thus, based on the layout of other monasteries and what was hinted at in the sources, I was able to extrapolate where the scriptorium might logically have been. Logically it was somewhere away from excessively hot or moist conditions that would be harmful to the parchment, while also near the library or room in which the books were stored.

Another important question that needed to be answered was how the rooms were adorned. The sources gave an idea of the general conditions of the room as well as the tools and furniture that equipped it but gave no indication as to how and if the rooms were decorated at all. Given the widespread seriousness that permeates all the sources and the emphasis that was placed on devotion to work, it seemed most plausible that the scriptorium would be austerely decorated with very little gild or decorations on the wall. All focused was to be placed on the skillful and correct production of the texts, so the room in the model was devoid of all decoration save for what was painted on the pages of the manuscripts.

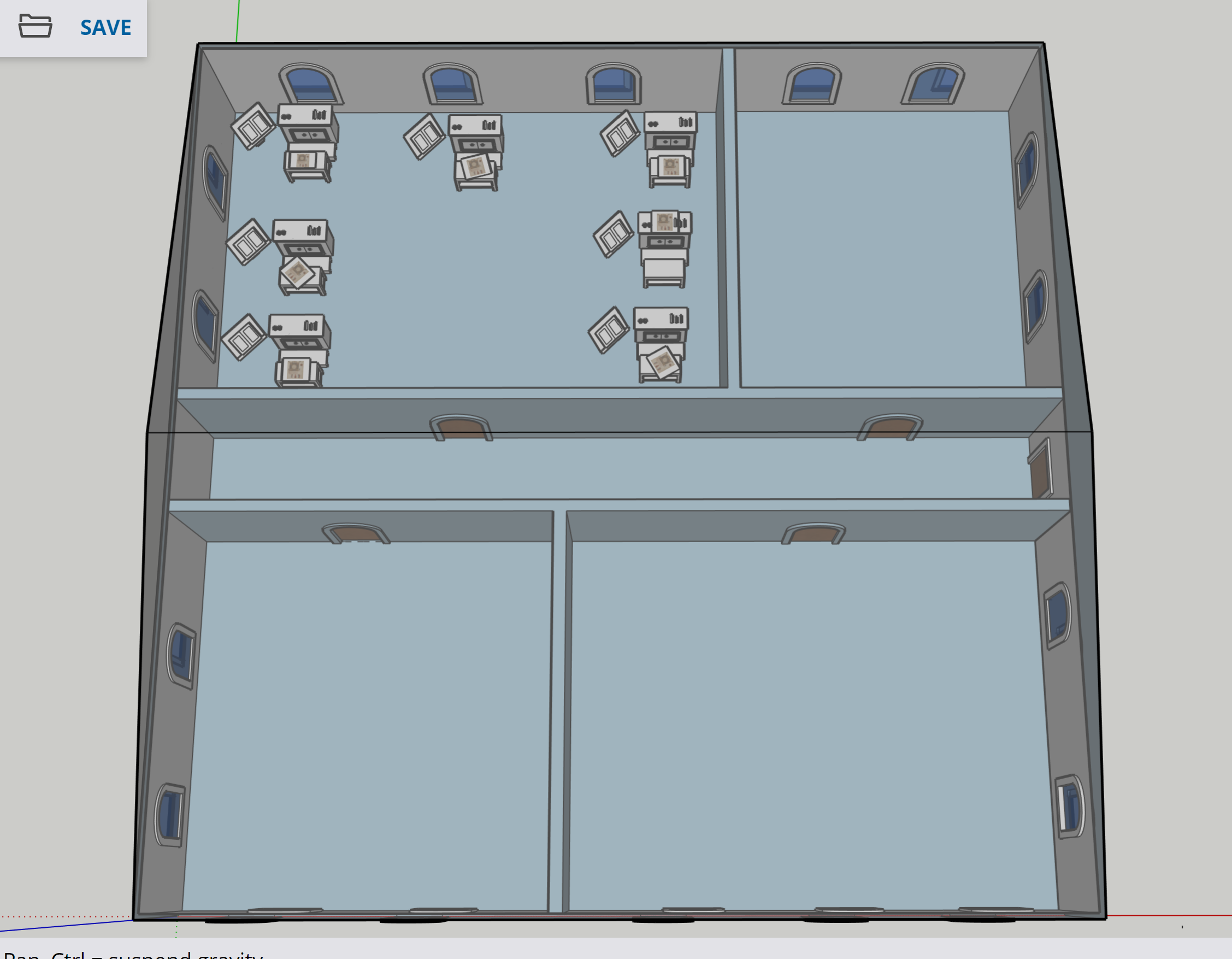

Once the data about the scriptorium had been gathered, it was then time to input the information into Sketchup and begin modeling the space. Because research revealed the scribes work was largely a solitary endeavor, the first step was to model the individual station for each copyist as that was where the majority of their focus was. Each desk needed to contain adequate supplies to allow a copyist to work with minimal interruptions or interactions with others, Figure 4 shows a close up of one such station. These desks where then integrated into a larger model that contained the room of the scriptorium. Once that room was situated according to interpretation of the information, the scriptorium was them placed inside of a larger building and put into the broader complex of the Studious Monastery itself. As the model became wider in scope it became more subjective because of the lack of information available. There was a relative wealth of information about the tools present on a scribe’s desk that allowed them to be placed with a certain degree of confidence, compared to the creation of the entire missing auxiliary building which contained the scriptorium itself. The use of Sketchup was advantageous for this project as it allows the scriptorium to be seen from more than one angle and to be put into context in relation to the surviving abbey at Stoudios.

Though the majority of the visualization was based on information from the available primary sources, there were still aspects of Byzantine space that were difficult to visualize. This is largely because of the lack of extant information about the scriptorium at Stoudios, or Byzantine scriptoriums in general. As a result, there were some decisions about the creation of the model that had to be subjectively made, namely the location of the scriptorium within the monastery. While it was difficult to make some of these decisions, examination of the materials at hand coupled with careful extrapolation from other similar buildings made it possible for me to feel confident in my creation and interpretation of the model, how the space was laid out, and how the scribes were situated within it.

Research Findings

With the creation of the model, several important discoveries about the scriptorium were made. One of the first things that became apparent pertained to the people who worked in the space and how. Namely that even though there were usually several people who worked together in the space, their work was done nearly entirely independently. In fact, they had to keep silent in order to concentrate, lest face repercussions from their superiors.[7] This fact was especially important in the creation of the scriptorium, because it required for there to be multiple copy stations in the room but dictated that they would all be spaced and set up in a way that was focused on the individual to minimized distractions and interactions with others. Additionally, not all of the copyists in a scriptorium were necessarily members of the monastic community. A book illuminator in Byzantine Egypt in his letter mentions that he dealt with people who were not officially connected with the scriptorium, but instead acted as freelance illustrators.[8]

With a better understanding of who was in the scriptorium and how they worked, the manuscripts that have survived into present day are better able to be put into context, especially since the scribes themselves seldom left personal traces in their works. The copyists primarily worked on their own. Even though there were sometimes separate rubricators, copyists, illuminators, correctors, and binders it was not uncommon for the main scribe to also do the illustrations and the rubrications in the manuscript they were working on.[9] So even though there were many people working in a scriptorium, the work done and the environment it was done in was far from friendly and collaborative. Instead the focus was on faithful reproduction of the text above all else.

The model also shows the conditions in which the manuscripts were produced and how the scriptorium operated since there are woefully few surviving sources. Other than the occasional note in a colophon complaining that they were cold and the ink was freezing in the inkwell or that the dinner hour was a long way off, the scribes were so faithful to the texts that there is very little record of their impressions.[10] From this commentary the layout of the room can be pieced together. The scribes would have worked in rooms devoid of a fireplace or other heat source, because of the risk it posed to the priceless materials they were producing, which the model highlights with the noticeable lack of a fireplace or stoves. These complaints shed light on the long hours and dreary conditions in which the scribes worked. Those responsible for creating works of great beauty and importance were heavily taxed by their work and not given the opportunity to appreciate the fruit of their labor. Rather, the production was an act of devotion in itself.

Another aspect of manuscript production highlighted in the model was the way in which the scribes wrote. The book scribes were copying from was placed on a stand for reference. On the desk were several different tools including a quill or a split reed to write with, a pen knife, the different inks and an inkwell, as well as miscellaneous tools like a compass to facilitate perfect circles when adding artistic details to the pages.[11] While each copyist sat on a bench in front of a table, they did not write on the desk. Rather, they wrote with the parchment or vellum held on their lap. This process was shown in illuminations in manuscripts that depict famous authors at work, and further elaborated in Metzger’s The Furniture in the Scriptorium at Qumran, in which he discusses, based on the archaeological remains, that scribes had a board on their lap to offer a smooth writing surface, and sat with their feet on a small platform that raised them approximately six inches and made for a better angle to write at.[12] Both the small platforms and the lap desks were present in the archaeological remains and in the illuminations, see Figure 5 for an image of St. Gregory at work writing his Homilies. These furnishings were also incorporated into the model of the Stoudios scriptorium as the writing process would have doubtlessly been similar. Both the footrest and the writing board can be seen in Figure 4 above.

The visualization of the Stoudios scriptorium answered some of the initial project questions about the space itself and the people within but has also inspired follow up questions for further historical research. Now that the scriptorium has been furnished, a next step would be to look further into how the spaces would have been decorated. Or if they would have contained any decorations and embellishments at all. Given the general austerity, or perhaps dourness, that seems to permit the accounts given by copyists, it is possible that the spaces remained undecorated.

Further research might also look into what and how many people would have had contact with the books produced in scriptoriums. Did these texts mainly stay within the monastery they were produced in, or were individuals outside of the monastic community able to view them also? It seems most likely that unless the books were commissioned by an outside patron they would stay inside the walls of the monastery, but there is no guarantee that is the case.

Conclusion

There are still a lot of unknowns about the scriptorium at the Stoudios Monastery, but this model serves to start the conversation about what the space would have looked like and how it would have operated. Even as one of the most important and well-known manuscript producers in the Byzantine Empire, there is still woefully little information available to help understand what the space looked like, or even where it would have been definitively located. But, by modelling the scriptorium with the use of primary sources, we are able to place the abstract complaints about a lack of heating and long hours into context that helps to better understand the lives of the people who produced such elaborate books. As well as to face the grim reality that their work was often far from glorious. The spaces that produced these elaborate pieces of art in actuality were very austere and formidable spaces focused on devotion and work rather than the beauty and joy that these books would bring to people both as decorative objects and as devotional tools.

Now that this initial study has been completed, further research might inspire one to look into the processes involved in the creation of manuscripts or tracing the supply chain for attaining all of the materials needed to produce a manuscript. By learning more about all of the steps of production and all of the individuals involved in the process, we are better able to understand how scriptoriums functioned and how the Byzantines interacted with the books that they produced.

Works Cited

[1] Paul Veyne and Arthur Goldhammer’s A History of Private Life: From Pagan Rome to Byzantium provided valuable insight for this project as it cites numerous primary sources and offers commentary on them.

[2] Veyne, Paul, ed. A History of Private Life: From Pagan Rome to Byzantium. Translated by Arthur Goldhammer. Vol. 1. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2003.: 540-41.

[3] Abt, Jeffrey, and Margaret A. Fusco. “A Byzantine Scholar’s Letter on the Preparation of Manuscript Vellum.” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 28, no. 2 (1989): 61-66. Accessed February 20, 2020. https://www-jstor-org.proxy1.cl.msu.edu/stable/3179480.

[4] Thomas, John, and Angela Constantinides Hero, eds. “Theodore Studites: Testament of Theodore the Studite for the Monastery of St. John Stoudios in Constantinople (Trans. Timothy Miller).” In Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents: a Complete Translation of the Surviving Founders Typika and Testaments, vol. I. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2000: 67–83.

[5] Metzger, Bruce M. “The Furniture in the Scriptorium at Qumran.” Revue De Qumrân 1, no. 4 (4) (1959): 509-15. Accessed February 20, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24599183.

[6] Thomas, John, and Angela Constantinides Hero, eds. “Theodore Studites: Testament of Theodore the Studite for the Monastery of St. John Stoudios in Constantinople (Trans. Timothy Miller).” In Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents: a Complete Translation of the Surviving Founders Typika and Testaments, vol. I.: 70.

[7] Veyne, Paul, ed. A History of Private Life: From Pagan Rome to Byzantium. Translated by Arthur Goldhammer. Vol. 1. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2003.: 541-42.

[8] Parássoglou, George M. “A Book Illuminator in Byzantine Egypt.” Byzantion 44, no. 2 (1974): 362-66. Accessed February 20, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44170449.

[9] Veyne, Paul, ed. A History of Private Life: From Pagan Rome to Byzantium.: 541-42.

[10] Veyne, Paul, ed. A History of Private Life: From Pagan Rome to Byzantium.:541-42.

[11] Veyne, Paul, ed. A History of Private Life: From Pagan Rome to Byzantium.: 541-42.

[12] Metzger, Bruce M. “The Furniture in the Scriptorium at Qumran.” Revue De Qumrân 1, no. 4 (4) (1959): 509-10.

Figures Cited

[1] Lowden, John. Early Christian & Byzantine Art. London: Phaidon, 2012.: 288

[2] Photo of Stoudios Ruins by Gabriel Rodriquez for Media Center for Art History, Department of Art History and Archeology at Columbia University, via Artstor, SSID: 23076092

[3] Metzger, Bruce M. “The Furniture in the Scriptorium at Qumran.” Revue De Qumrân 1, no. 4 (4) (1959): 511. Accessed February 20, 2020.http://www.jstor.org/stable/24599183.

[4] Ivey, Katelin. Stoudios_Monastery_Final. Sketchup. Created April 28, 2020.

[5] Lowden, John. Early Christian & Byzantine Art. London: Phaidon, 2012.: 292